Heidi Ross, Photographer | Nashville: Scenes from the New American South

Mennonites at Mas Tacos. An outtake from photographer Heidi Ross’ new book, Nashville: Scenes from the New American South.

In those low-down days after David Bowie died, a meme went around that said something to the effect of, Don’t be sad: think about how lucky we are. The Earth is billions of years old and we somehow managed to score a terrestrial tour of duty that overlapped with Ziggy Stardust’s.

This really resonated with me for some reason. Lately, I’ve been using a version of it to qualify what many of us who live and work in Nashville circa 2019 are feeling right now: how lucky are we to find ourselves here during the city's gangbuster renaissance?

If I ever need visuals to back up this claim, I’ll reach for a copy of Nashville: Scenes from The New American South, a new collection of photography by my friend Heidi Ross, created in collaboration with her good friend, author Ann Patchett, with a forward by Nashville-based historian Jon Meacham. It’s a gorgeous book, filled with photos of dynamic Nashvillians — many of whom I know well and love dearly — whose work and vision make Nashville such an incredible place to live.

The first time I read it, I cried.

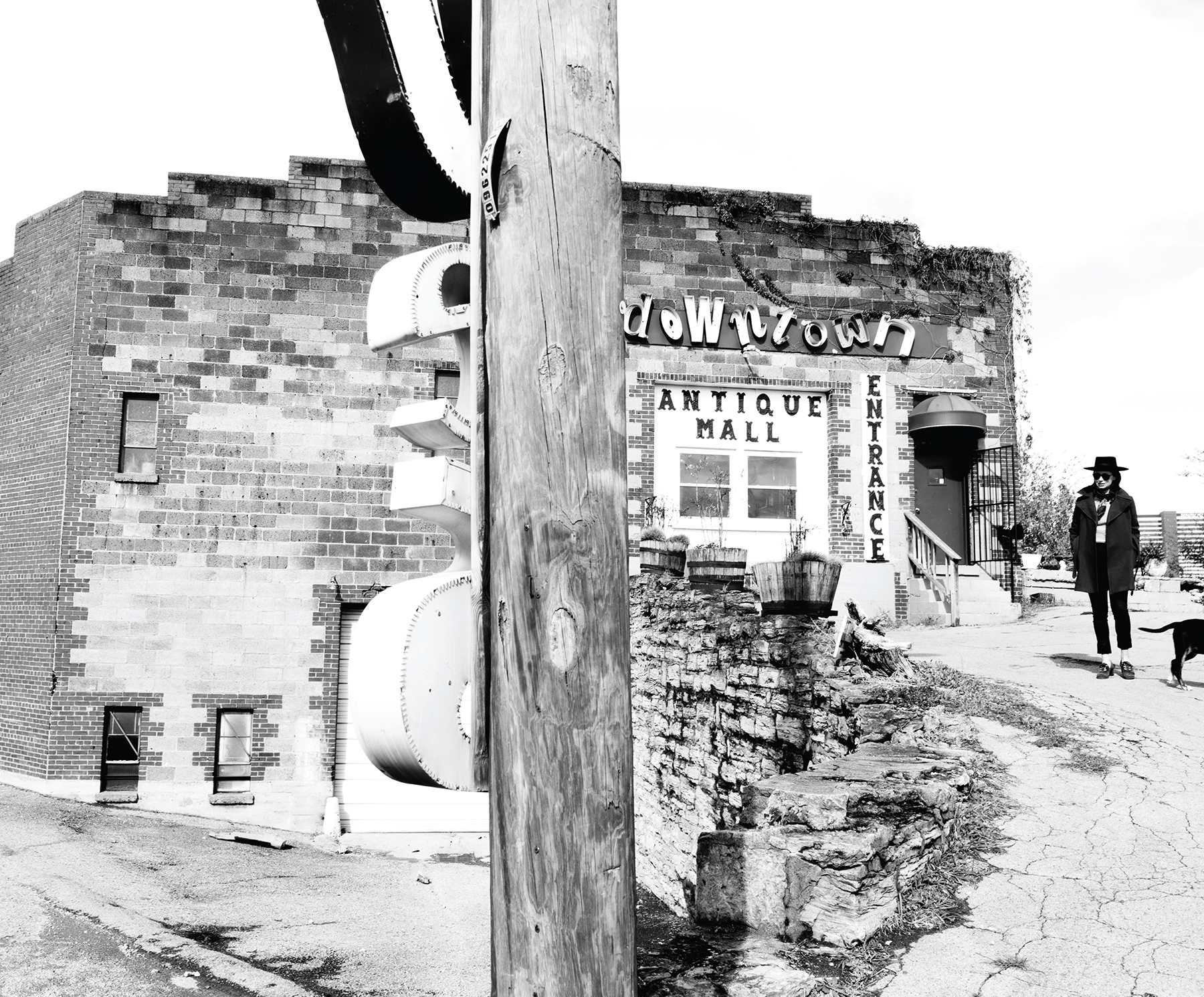

Outside the Downtown Antique Mall.

On a very personal level, the book overwhelms me with gratitude for the friendships I’ve made during my 15 years in Nashville. Enjoyed through a more macro lens, it gives me an enormous sense of pride in the creative community that’s flourishing in my adopted hometown and the impact that this growth has had on how the city is perceived by those on the outside. “It City” didn't get that way by accident; it came from a lot of hard work. Nashville is a community of self-motivated ass-kickers who make things happen and get. it. done.

Another reason for my wet cheeks: I’m so proud of Heidi. Talk about kicking ass.

She shot for over a year and a half to capture the diverse lot of images that ended up in the book, with many more excellent photos sidelined for no other reason than a lack of space. I know how much time and hard work she put into this project, and it shows. She crushed it.

In addition to being a brilliant photographer, Heidi is a terrific writer — funny and clever and honest and dry in a way that never feels snarky. When I decided to post about Scenes from the New American South, there was no way I was going to pass up the opportunity to have her voice featured on TCR.

Heidi Ross

When I think about big projects like this book, with its expansive subject matter and breadth of images, the editor in me can’t help wondering about the photos that didn't make the cut. For this piece, I asked Heidi to share her thoughts on what got left on the cutting room floor, so to speak. The shots featured here are some of those outtakes, including an incredibly beautiful portrait of famed cellist Yo Yo Ma that she captured during his rehearsal at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center downtown. Her recollection of that day is pretty special.

Dammit, Heidi. You made me cry again.

I get ridiculously anxious when I try to talk or write about Nashville: Scenes from the New American South in exactly the same way I was anxious the whole time I was shooting it. It was such a compressed project in terms of time, with such diverse expectations, including my own. What I wanted, needed, above all else was to know I had done right by Nashville — or at least not failed Nashville — and to me that meant fighting any impulse to make Nashville look like One Thing.

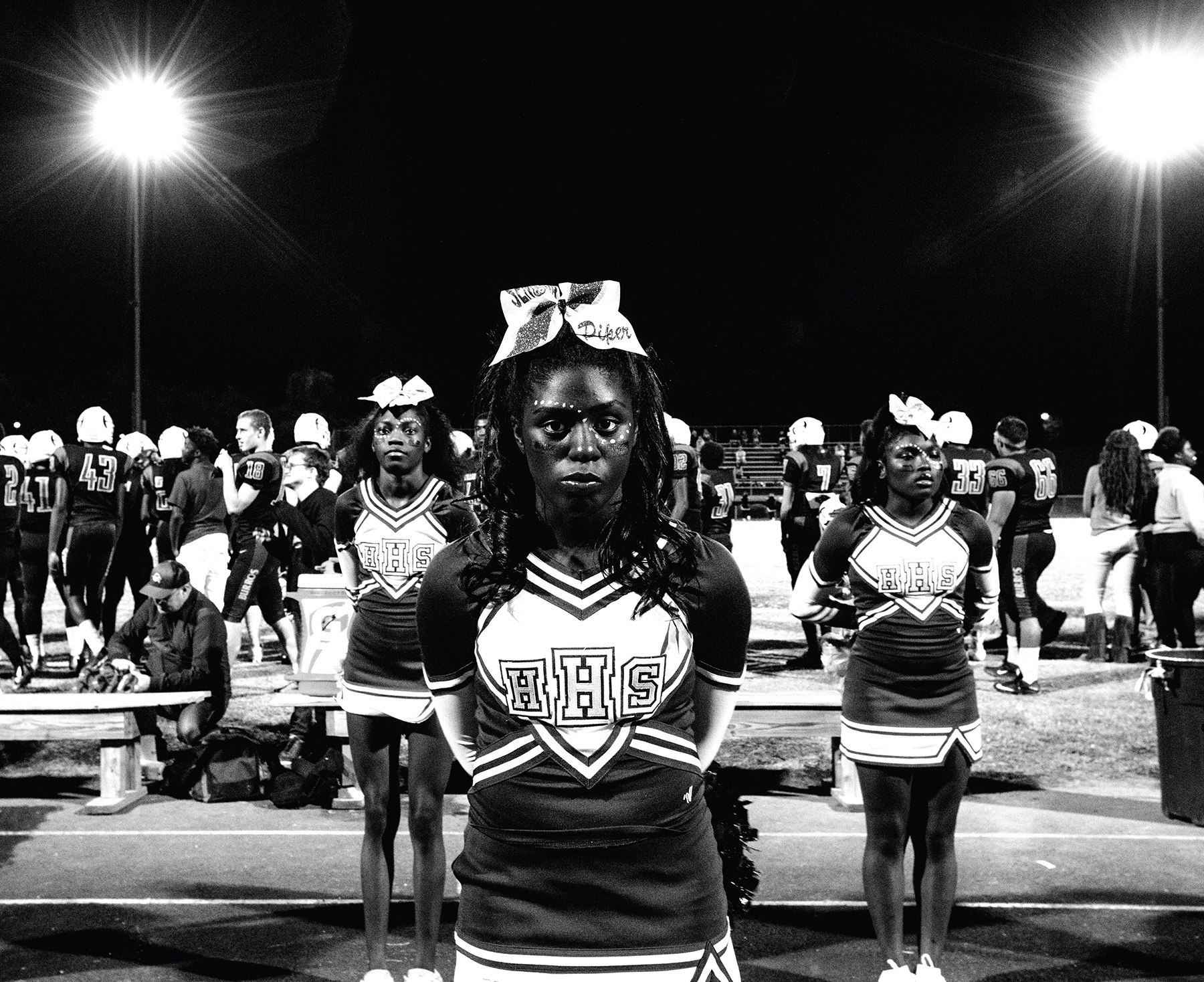

A city of people, any city of people, is not an Instagram account or a lifestyle brand. Everything that made this project challenging is what makes our particular moment in this time and city challenging. It can be hard to see past the Nashville-as-brand that has so caught the national imagination at a time when not only magazines and newspapers are projecting that curated version of the city and its people, but when we are enamored of the curating power of social media as individuals. I felt such a responsibility to un-curate the city aesthetically, while knowing full well that any photographer can only see through her own eyes, which will inevitably give the work a certain look.

My eye is the eye of a fly on the wall, always, the eye of someone at a bit of a distance. I’m removed physically, but not emotionally, from everything I shoot. The emotional closeness is actually what makes the physical closeness hard. I don’t have a buffer. What I do have is a constant experience of seeing everything from multiple perspectives at once, which is overwhelming in general but also appropriate for this particular project. Shooting Nashville forced me to live in a place, literally and figuratively, where I felt invasive and uncomfortable and lucky and very afraid of fucking things up every single day for more than a year straight. It was an opportunity and a privilege on a level beyond anything I’d experienced before and quite possibly beyond anything I’ll experience again. I did not step foot out of the city for more than a year and a half, and that will do funny things to you (I’m sitting in New York writing this and lord, let me tell you, when you weep openly at the sight of Duane Reade the way you secretly wept at the face of Yo Yo Ma, you need to get out more).

When people ask me how I feel about the book, the honest answer is I don’t know yet. I will know in a year or so. The experience was more than I could absorb in the moment, but each experience within it was saved, somehow, for later. They have begun to surface only now, after they’ve passed, little snack-size Ziplock bags of perfectly preserved treats. I’m having the experiences now, after they happened. The Nashville book is a very well-stocked snack drawer. The outtakes, especially, have this effect on me.

Obviously, not every shot was going to make it into the book or be to the editor’s taste or be the right fit overall. It makes sense that the outtakes weren’t in-takes. Yet Yo Yo Ma’s face in an unstaged portrait as he sat on the Schermerhorn’s stage at rehearsal the first day I began shooting the book is as Nashville to me as anything in the book. I had parked on the other side of the Cumberland (as I was to do many times, it turned out) and walked over the John Seigenthaler Bridge to shoot him, Edgar Meyer, and Chris Thile. One of the great gifts of my life, not just of the book, was that I got to enter the symphony hall when it was dark, quiet, and almost entirely empty and hear the sound of Yo Yo Ma’s cello filling it. For me, that sound is in his expression in the portrait. There were so many moments like this, gifts unimagined that could not have come about any other way. There’s no reason for a portrait of Yo Yo Ma all by himself to be in a book about Nashville. But it’s in my Nashville, indelibly.

My Instagram account will probably never look very curated. I tried once and failed almost immediately. If there’s not room for everything to be free and to be different, I feel a distress completely out of proportion to what is reasonable to feel about an Instagram account. Many times since the book came out, people have asked me which photographs in the book are mine; even though I’m listed as the photographer, they often think some of the images are archival or shot by someone else. This secretly (or I guess openly, now) makes me proud. I can’t bring myself to want things to look just one way. I don’t want to make things match.

Yo Yo Ma

It can be tricky in Nashville right now, if you’ve lived here longer than five minutes, to see past the matching-ness on the surface that is suddenly everywhere and sky-high. Unmatched Nashville is still there, though. It’s just harder to get your eyes around it all at once. It’s hard to hold the subtle and the loud at the same time. But I think it’s our job, and in fact it’s a job we’re incredibly lucky to have. It’s how I feel about these photos, about the book, about the city, about all of it.

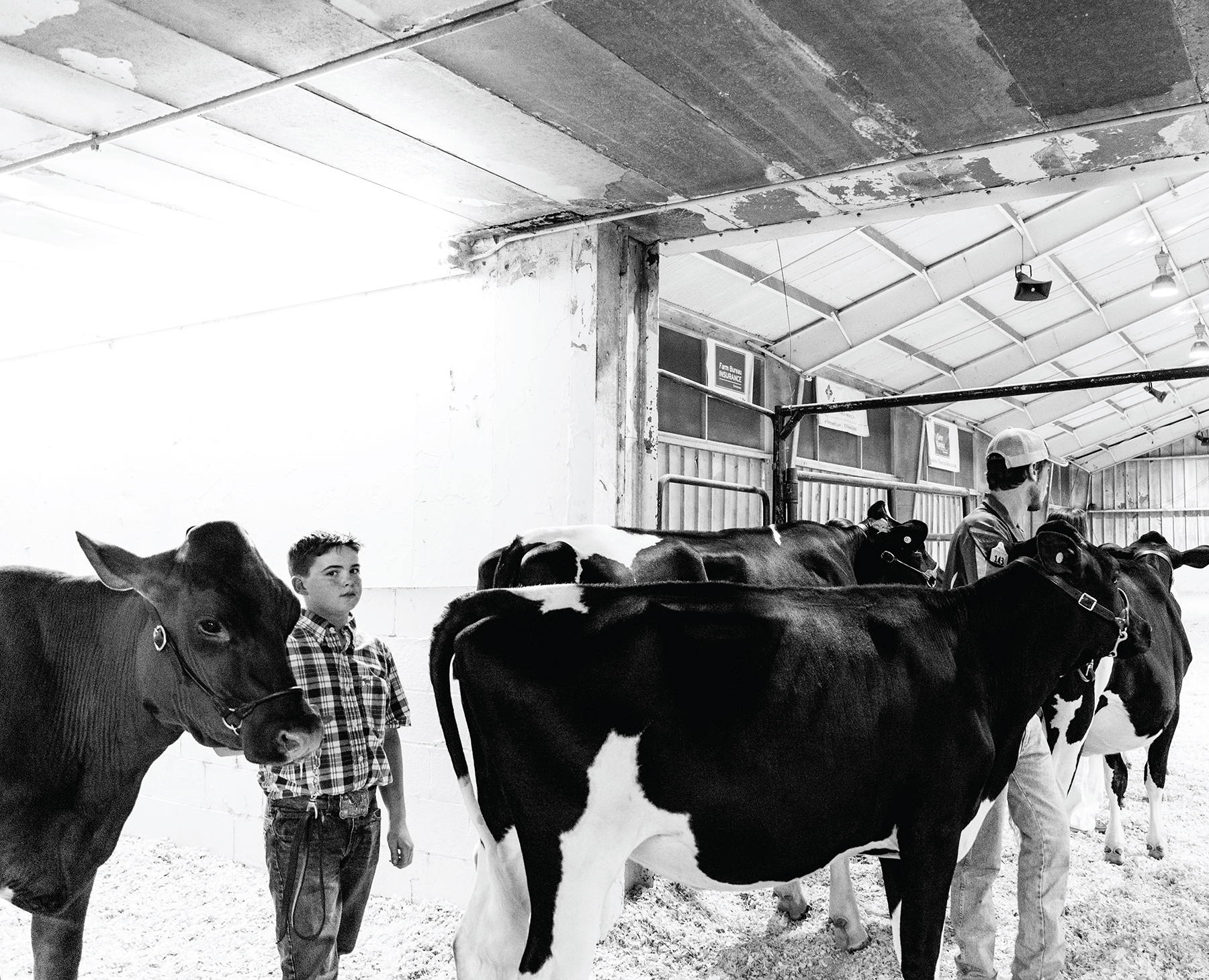

Here, then, are a few of the photos that didn’t make it in — things that didn’t match, things that belong as much as anything else ever does. To you as much as anyone, here as much as anywhere.

Love,

Heidi

Heidi prefers to let the photos here speak for themselves. However, she did have a story to share about this one, which was taken as she walked over the John Seigenthaler Bridge after a memorable shoot at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center. “The woman on the red bike was shot the same day I shot Yo Yo Ma, as I walked back back over the bridge. It's the one I wanted to end the book with. The editor chose to end with a photo of the club, The End, which is fun and made sense. But the woman on the bike will always be the last page to me. She rode past me twice, the second time more slowly, laughing, and shouting, ‘You can shoot me for your portfolio!’”

Nashville: Scenes from the New American South is available at many fine stores in Nashville and beyond. If you’re shopping for it locally, we suggest going straight to the source: Parnassus Books, the Nashville book shop owned by Heidi’s friend and project collaborator, Ann Patchett.